Supervision

Supporting the IMG registrar

It is well recognised that IMGs face multiple challenges to successful passage through, and completion of, GP training. GPSA recognises the important role that GP supervisors play in supporting IMG registrars and other GPs in training. For consultation skill teaching, please also refer to the Consultation Skills Toolbox and the Consultation Skills Teaching plans.

Principles of IMG Supervision

It is well recognised that IMGs face multiple challenges to successful passage through, and completion of, GP training. GPSA recognises the important role that GP supervisors play in supporting IMG registrars and other GPs in training. For consultation skill teaching, please also refer to the Consultation Skills Toolbox and the Consultation Skills Teaching plans.

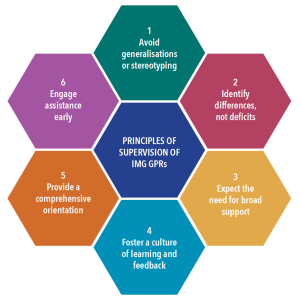

There are a number of broad principles that should guide the supervision of IMG GP registrars. While these are appropriate to all registrars, they have particular importance for IMGs.

AVOID GENERALISATIONS AND STEREOTYPING

International Medical Graduates are not a homogenous group, and have a wide range of knowledge, skills, attitudes, experience, and backgrounds, even within the same cultural group. This may sound obvious, but it is critical to avoid generalisations or stereotyping, and for supervisors to regard every IMG as unique. Where issues arise, it is critical to specifically ‘diagnose’ the problem (educational, personal etc.), rather than generalising it as being ‘cultural’ or ‘language’.

IDENTIFY DIFFERENCES, NOT DEFICITS

While often associated with posing educational and training challenges, IMG GPRs can bring a wealth of positive skills, attributes and expertise to GP training and the general practices in which they train. Such positives include:

- A broader world view

- Experience of alternative health systems (often in disadvantaged communities)

- Specific clinical skills

- Second (or third) languages

Resilience to setbacks - Reflecting this, a recent paper on supporting

- IMG GPRs argued that the focus on supervision of IMG GPRs should be on ‘difference’, not ‘deficit’. Furthermore, the authors stated that labelling IMGs as having learning needs was unfair without also acknowledging their unique strengths.

EXPECT THE NEED FOR BROAD SUPPORTS

The IMG GPR is may need increased support across all facets of training – educational, pastoral, personal and professional.

While the transition from the hospital to the general practice setting is potentially highly challenging for all registrars – characterised by a breath of clinical problems, relative independence of decision making, time pressures, management of uncertainty, new practice systems, financial and billing issues – this challenge is likely to be exacerbated for many IMGs.

It is essential that the supervisor of IMG GPRs is willing to take on this broad responsibility, and to be overt about their support role in all aspects of the registrar’s development.

FOSTER A CULTURE OF LEARNING AND FEEDBACK

It is vital to foster an open and honest culture of teaching, learning and feedback in the practice.

Supervisors should use a broad range of teaching methods and focus on skill development, rather than clinical knowledge. It may be necessary at times for the supervisor to have challenging conversations with the IMG GPR on sensitive areas like cultural norms and communication issues. Thus, it is critical for both supervisor and registrar to agree on a process for frank feedback, while also maintaining a culture of mutual support.

PROVIDE COMPREHENSIVE ORIENTATION

One of the key planks in effective supervision of the IMG GP registrar is provision of a comprehensive orientation at the commencement of the training term.

In addition to the usual clinical and administrative benefits, there is evidence that effective orientation of IMGs can increase their sense of professional identity, morale and belonging. IMG registrars are likely to benefit from discussion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, as well as Australian culture more broadly, and community support. This may also include an orientation to the IMG registrar’s partner and family.

ENGAGE ASSISTANCE EARLY

Supervisors need to engage appropriate support from their regional training organisation, or elsewhere, when performance issues arise.

Performance issues for IMG GPRs are often complex and may require specialist input. Supervisors should therefore have a low threshold for seeking guidance from the registrar’s medical educator.

Topics

CULTURAL

There are multiple issues related to cultural differences that are challenges for IMGs.

Resource

- VIDEO: How do cultural values and perceptions impact on clinical care?

COMMUNICATION

It is well known that some IMG registrars have significant language issues that may impact on satisfactory communication, both with patients and peers. IMG GPRs may struggle with fluency and structure, and comprehension of colloquial English. Specific scenarios that require the use of specific communication skills can also be challenging, for example managing the angry patient, and saying no.

Resources

TEACHING AND LEARNING

There are many aspects of teaching and learning that may be challenging for IMGs. These include cultural approaches to learning, approach to feedback and help seeking behaviour.

Resources

Resources

A range of practical tips for the supervisor to support the IMG GP registrar in the practice in the following resources:

Date reviewed: 21 November 2024